Good teaching is telling stories

I am certain that you cannot teach via test and that all people are teachers, not just Teachers. But I am constantly refining this thinking by asking myself, “Why don’t tests work? Why is the practice of teachers and schools inherently limiting?”

I think I’ve found the answer in the idea of stories.

1. Math is best learned through stories. Math in a vacuum is all theoretical and very few people need or want to think this way. What we really need is a sense of numeracy which means being able to ask mathematical questions to understand our world better. This is not learning rules for geometry. This is learning to incorporate math into the stories we tell ourselves of the world around us. Beyond Numeracy by John Allen Paulos, helps us ask questions that can be answered with stories (what happens to the number infinity?) rather than equations.

2. Writing is best learned through stories. Why teach a kid to write a paragraph about something that is not important to them? No writer ever wrote well about something they are not passionate about. So why expect kids to do that? Everyone has a story. Newton’s story was of gravity—something drops but why and then what happens? Eric Foner’s story was about slavery—American history is the story of the ripple effect of slavery on national identity. The best writing teachers don’t teach writing—they teach students how to find the story that matters to them.

3. Spelling is best learned through stories. I learned this fascinating analysis from the article by literacy expert Misty Adinou titled Why Some Kids Can’t Spell. She writes, “Only about 12% of words in English are spelt the way they sound. But that doesn’t mean that spelling is inexplicable, and therefore only learned by rote. It means that teaching spelling becomes a fascinating exploration of the remarkable history of the language—etymology. Some may think that etymology is the sole province of older and experienced learners, but it’s not. Young children are incredibly responsive to stories about words, and these understandings about words are key to building their spelling skills, but also building their vocabulary. Yet poor spellers and young spellers are rarely given these additional tools to understand how words work and too often poor spellers are relegated to simply doing more phonics work.”

4. Adult success is contingent on our ability to tell stories. You get hired based on your ability to tell a cohesive, engaging story of your career. (The world is complicated, but you made a path for yourself.) You create resilience by telling yourself stories about how you got to where you are and what you did to get yourself there. (The world is difficult but you have control over things that matter to you.) Stories are how we control our sense of wellbeing, so learning through stories as a child gives us the life skills we need as adults.

5. National curriculum doesn’t work because stories work best when we are ready for them. I convinced my parents to take us to a bunch of R-rated movies when I was a kid. I remember that the only thing I understood in the movies was the sex (yep, there it is) and the violence (hey! that killed another person!). What I didn’t understand was the story. Because it was too unconnected to my own experience to make sense to me. We can learn about new things with stories that bridge the world we know and the new world we are exploring. But with no appropriate bridge there is no learning.

Kids need individualized learning because we tell stories in a way that is particular to us. We look at the audience’s reaction and adjust accordingly. A baby does this, which is why learning social skills is innate. A kid with a good sense of humor does this, which is why good comedians have been telling jokes since they were five. The gift of a writer is that there is an internalized audience that allows the writer to do both sides of that give and take.

Telling a story is personal and all about connection.

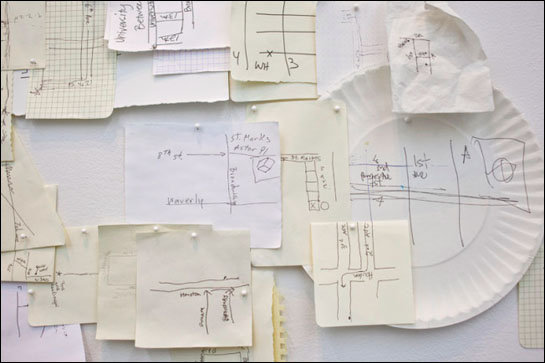

Nobu Aozaki did an art piece about how differently each person gives directions. The art becomes a visual argument for the idea that each person learns through stories differently. We don’t even tell the story of how to get from one place to another in a standard way. Which is why standard eduction through stories doesn’t work.

You cannot teach through stories with a 9:1 teacher student ratio. Each kid needs a personal story to learn what they want to learn when they are ready. And each kid needs to learn to tell stories in their own style, but there is no grading system for that, so, of course it doesn’t work in school.

I maintain that teaching can be done ‘via test’ – for example, auditions provide a test. Practicing for audition teaches. The product of successful testing, then, is a standard for solo (or accompanied) performance.

Will it perfectly translate to concerts? Not quite, perhaps. For example, it is increasingly widely acknowledged that physical appearance is important to the reception of concert performance, but that is sometimes screened out in auditions. However, one can still teach musicianship via audition.

The challenge is to create a test that accurately scores the desired skill in a reasonable time frame; reproducible and generalized across the relevant population. Many tests fail in various aspects of this.

Right on again, Penelope. I think this is why even using a Waldorf curriculum at home didn’t fully meet my children’s needs. Although stories are used to explore and learn about math, history, science, and language arts, if my children weren’t yet ready for the stories selected for that year, it didn’t resonate.

I’d love to read a post about how to implement the right stories at the right time. This is what I’m constantly trying to figure out now that we are heading into child-directed territory…

I like stories. And I enjoyed this post. It reminds me of that book – Made to stick – and how sometimes its the seemingly irrelevant details (an apple) that make all the difference in remembering and internalizing something (gravity).

You mean a 9:1 student:teacher ratio.

There are many different ways to present material to a student to make the experience more meaningful and memorable. STEM subjects can easily be made to be the most dry and ‘disconnected from reality’ material to be consumed by a student. And I’m not even talking about a teacher’s ability to communicate the ideas and principles of the material to the student. Typically the subject material is presented in a curricula that’s been laid out in a linear and logical format. As an example, all the derivations and results that help to explain the properties and interactions of an element, compound, or naturally occurring substance in a given environment. Basically, many times the instruction curricula is a compendium of answers to questions which we don’t know or know why they were asked in the first place. That’s why I think it’s not only important to show examples of theory not only being given relevance by way of practical example but also including why the subject material is relevant by knowing the background story.

I think it’s important to know and understand the process of discovery to give the subject material meaning. The learning process is enhanced when a human element is included such as understanding the questions asked and why they were asked in the first place. A different way of instruction would be to study the people who carried out the research and their research techniques and results rather than only studying the subject field itself. This type of study would include the knowledge of the field in which people researched and practiced as well as illustrate the successes and failures of these people to give a more human perspective and story of a subject.

Yes. What IS it about stories that makes them so powerful?

Postmodernism idea about “narratives”: how the ruling class tries to make its story the only one in town.

Corporate culture: getting the corporation’s story straight.

Censorship: Preventing other people from telling their stories.

The “Interview Tip” post….very helpful.

It doesn’t matter how good your intentions are if the people hiring you don’t trust your story. The hard part is taking a complicated story, boiling it down, and getting your true motives and intentions across clearly, while nervous and off guard. It takes practice to gain confidence in telling your story.

A good teacher gives you answers a great one inspires you to search for them.

We don’t ‘teach’ through tests. We test to see how much of what has been taught has stuck with the student. Tests are a useful tool to measure comprehension and retention. I’m not saying tests are necessary or the only way however, just that they clearly are not meant as a manner of teaching so much as a tool of teaching.

Tests for the sake of testing are not particularly useful – but if the tests are more like a “milestone” it can really push students to dig deeper and explore their limits.

As far as ‘we’ – the mantra I was taught was ‘start with the assessment.’ In essence, design the curriculum/lesson with what you want a student to be able to accomplish at the end and then figure out how to assess it. There should also be a baseline assessment and some intermediate assessments. These are teaching materials, not accessory to the learning process.

Of course, this makes more sense, generally, if there are multiple students learning the same basic material.

The amazing insight that storytelling is the fundamental key to teaching and learning is typical of the basis of pedagogical fads. Perhaps the educational theorist has experienced a breakthrough in a personally difficult matter, and has realized a commonality with one’s previous breakthroughs. Or ones peers may all come to the same startling insight. A dab of fake research and an accretion of confirmation bias will always bear out one’s insight. From there the next step is curriculum design. This curriculum design may succeed for some subjects, but will fail utterly for others.

This is the way we get to 33 kids in a class with one teacher not being taught any math but being asked instead to tell stories to each other about numbers. Math skills never develop, only verbal skills, and the work groups become social competitions where the least aggressive don’t participate at all.

Six years later, every child whose parents didn’t already seek remedial help after school now requires it to continue grade-level work, because algebra is impossible without a firm grasp of arithmetic.

The bearer of the original insights inspiring the pedagogical theory never considered the idea that mathematics is a language in itself, with a reality of its own that does not require verbal fluency to experience. Requiring every bit of mathematics to pass through convoluted and wordy stories keeps students away from the world of numbers and functions. Some who otherwise might have been brilliant in mathematics will become entirely discouraged.

Likewise, if the only way students may be taught a foreign language is through Teacher telling stories about words in English, students will get only the most distanced appreciation of a language, but never any kind of fluency. Learning a foreign language requires not lengthy explanations but repeated practice. I recall repeatedly tricking our Latin teacher into lengthy digressions in English as a way to avoid the subject matter.

The same is true for music. Does the music student make up lengthy stories about Do and Re and Mi or does he listen to music, listen to himself, adjust his fingers, and play without speaking for hours? Storytelling may help to socialize and contextualize physical learning, but the learning itself must be done physically.

Requiring the entire curriculum to pass through storytelling shuts those whose strengths are non-verbal out of learning and allows those who have kissed the blarney stone to sail through any subject without learning anything.

Insights about the way people naturally learn are inevitably limited. People learn in a variety of ways. Application of such insights to the schooling system, without considering the system’s inherent strengths and limitations, is almost always a disaster. The worst pedagogy has come from the best intentions.

The insight or observation that story-telling is fundamental to human nature is as important now as it has been for centuries. Successful curricula in a variety of subjects have been developed around this principle. The pedagogical principle has been a part of storytelling since neolithic times. But it is not a one size fits all panacea for learning unless you want to limit your learning to those things amenable to the method.

indeed – story telling has its place and I love good stories. But it is by its very essence a verbal pursuit, and neglects all the other ways to learn. Abstract thinking is pushed to the edge, the development of logic remains woefully neglected. As such stories are the essence of human experience but so is the abstract. We don’t always need a connection to tangible things around us to think deeply. Fractions are not always best explained with the cake-example…

In first grade, before I pulled him out, my son said to me: “I get the idea of addition, and subtraction, and multiplication, and division. These are are all sort of operations that numbers perform on each other. Are there any other kinds of operations numbers can perform on each other?”

In school, math was still paragraph-long stories about mommy and baby hedgehogs that boiled down to “3+2=5.”

I told my six year old boy about exponents, square roots, factorials, and irrational numbers. He was fascinated. There would have been no way to communicate to him the things that fascinated him in a story form, and no need. He still struggles with the mundane in mathematics and yearns for the complex. He sees algebra as his reward for mastering arithmetic.

In my years as a teacher, I was taught and saw verified the fact that people don’t all learn the same way. I would not try to teach all children the same way my son learns, and I would hope to avoid having any startling insight of my own become an oppressive rule for others.

Life of Fred teaches math through stories.

redrock, when I read your post you seem to infer that stories or narratives exclude the use of abstract, logic, and symbolism to adequately convey an idea or concept to a student. Stories have their limitations without a doubt. However, I think if stories can be used to intrigue and inspire a student to further explore and ask more questions, then stories are important to that extent. That is, to “get the wheels turning” and “get the ball rolling” at the onset and during the learning process. I think both the stories and the abstract can and should be used together to varying degrees and times with the ultimate goal being achieved which is the student’s comprehension of the subject area.

I don’t think this is an absolute: story OR abstract. There certainly is an overlap, and I would rather call it context than story.

A great post! I homeschool my two boys, but am working on my MA in Elementary Ed (I wasn’t planning on homeschooling, but now we love it). I did a research project on How My Children Learn at Home, where I just watched what my children did all day and tried to make sense of it. I found that my sons are constantly making sense of the world through self generated stories. I also cited your blog in the paper, Penelope, thanks for all your work.

I struggled for years to help my daughter learn her basic addition facts. She memorizes all kinds of trivial facts about animals because she loves animals. But those math facts were just so boring! Many tears were shed by both mom and daughter over this issue.

She was almost nine years old before I finally hit upon a solution. I wrote her an adventure story (free online at http://www.scribd.com/doc/170328751/Adding-Adventure-to-Life) that starred her and her pet stuffed tiger and included all the basic addition facts. She read it with great interest a few times, and at last she knew her facts and was confident in them.

I’m a big believer in the power of stories.

Hi Penelope! What do you mean when you say “math in a vacuum is all theoretical”? I get all your points except that one. Thanks!