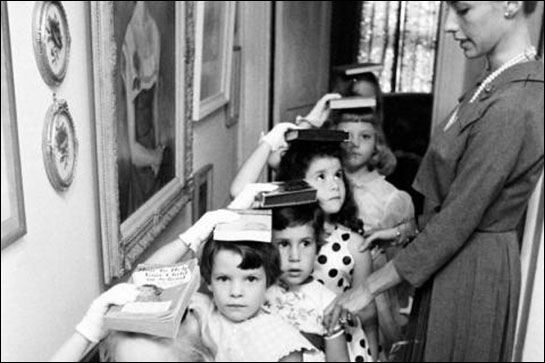

Careful with that language arts curriculum. Its original purpose was finishing school.

The word doomscrolling appeared for the first time in The New York Times, in an Opinion column about coronavirus.

The Twitter feed about the first appearance of words in the New York Times is fun because it’s about when a word goes mainstream. It’s the hockey stick growth equivalent for a word. (Hockey stick growth is the word for startup success that first appeared in the New York Times in 2008.)

Doomscrolling is different from a Wikipedia death spiral which is doing a deep dive into something that is not current news. You can tell a lot about a person when they hear a new word and ask “what’s the difference between that and xxx?” This is how we really learn to use language artistically.

Which is why language arts is not about using language artistically. Language arts is leftover from finishing school where kids learn letter writing, thank you notes, and other conversation pleasantry. Kids who care deeply about language probably do not go to finishing school because attention to language leads a person to ask sharper and sharper questions. For example:

What’s the difference between apple and peach is a question.

What’s the difference between ‘apple of my eye’ and ‘you’re a peach’ is a great question.

(My answer – I can’t resist – is that we treat one phrase as more intimate than the other. The mention of a body part that is actually an opening is what makes that phrase more intimate.)

Having the perfect word means we can make ourselves understood more clearly than we expected to be able to before we knew that word. Specificity could be particularly appealing to the angsty teens who constantly feel misunderstood. But I’ve found it appeals most to people born with a love of language.

You cannot convince your kids to love words if they do not. Just like you cannot get your kids who love words to love math instead. In my own family, my mom used to yell “five cents” for a five-syllable word. She did not instill a joy of large words in us kids, but we do love to yell “five cents” when one of us says a big word.

The opposite of loving language is speaking in cliches. But actually, people who speak in cliches can’t really communicate. They are mostly pretending to communicate and really just talking to talk. So I guess taking joy in language is wanting to really say something. The only way you can teach that is to actually talk to your kid. And then actually listen.

Which would mean the best curriculum for language arts is: How To Talk So Kids Will Listen and How To Listen So Kids Will Talk. Which brings me to what I always come back to when I think about curriculum: whatever it is that you want to teach to your kids, teach it to yourself first.

Your main point at the end is something I’ve been saying for years: unhurried conversation about many different topics cultivates excellent thinking skills and usually leads to good writing. Even people who don’t like to socialize still benefit from intentional conversation. It also strongly helps retention of knowledge.

The book “How to Talk to Your Kids” is fantastic. I second your recommendation. It’s helpful not just from a psychological and emotional perspective but as you said, fosters good communication. The theory of the book applies the adults, too!

I quoted the book title incorrectly but I meant the same book you linked. I read it 28 years ago.

Apple of my eye is more intimate, in my opinion, because it implies I am looking at you, I see you voluntarily, I like looking at you. Not just cause it mentions an opening of the body. “Apple of my nostril” or “apple of my navel” … just doesn’t seem to have the same ring to it.