Post-Covid evictions will be worse for education than Zoom

When the CDC placed a moratorium on evictions, 18% of renters had fallen behind during COVID and could be evicted. The CDC warned that we were on the edge of a homelessness crisis. Today that number is 14%. Yet the moratorium could expire this month, and renegade landlords are already pursuing evictions.

I got COVID in February 2020. I did not have enough breath to walk upstairs to my apartment without resting until August 2020. So it’s no surprise that it took me about 12 months to recover financially from all the lost income. During that time, I did not worry about my kid’s schooling. I worried about what if I died. Or what if I didn’t die and I just fell so behind in work that we didn’t have food? Or I felt so behind in rent that we got evicted? Fortunately, I live in the bluest of blue states, and multiple agencies contacted me because I had COVID and asked if we needed help with rent.

Having a 14% increase in homelessness will overshadow any other efforts we have made to improve education.

Even the Washington Post, which is the conservative version of The New York Times, has come down hard in favor of the CDC ban. Without the moratorium on evictions, the long-term damage is not only huge but also easy to quantify.

- By the time a homeless child is 8 years old, 1 in 3 has a major mental disorder.

- Homeless children have twice the rate of learning disabilities and three times the rate of emotional and behavioral problems, all of which make homeless students twice as likely to repeat a grade as compared with non-homeless children.

- Homeless children perform worse academically than children categorized as low-income — homeless children scored 10 percentage points lower on the state math and English tests than low-income students who were not homeless.

We are so precious about everyone’s right to school in the US. But there’s a more fundamental right: the right to housing. Which does not exist in this country. The right to a home is feasible and logical in our society. But giving all kids a safe home to live in with their family would be revolutionary in our country. So instead we talk about the right to an education because we know that won’t change anything.

For the last ten years, I’ve been saying that education reform is a red herring. What we should really talk about is housing reform. So if you want to make a difference in education, fight against evictions. The CDC is on trial nationwide, and the landlords have much better lawyers than the renters. But just like education and homelessness are local in the US, so can rental moratoriums can be local. There are examples all over the US.

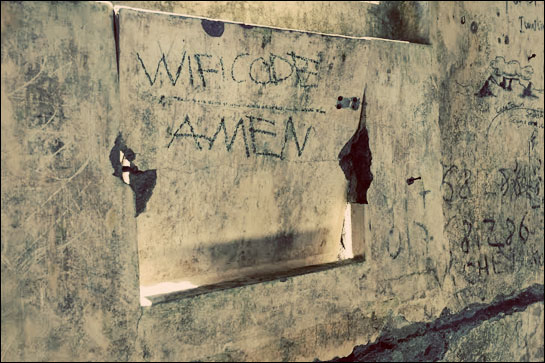

The picture up top is one Melissa sent to me while she was traveling. A church that provides free WiFi. She knows I hate vacation pictures, and I remember thinking this picture should not exist in a town where Melissa arrived by airplane to have dinner. Ten years later, living through COVID, the picture looks hopeful to me — part of a safety net at the local level. This may be proof that we can use any picture to support any opinion we have. Or it may be proof that we see what we want to see. Regardless, I want to see hope, and this is a moment of opportunity at the local level.

I propose it wasn’t COVID that created the problem this country has with evictions. It was the top-down, centralized response to it by the government. There was never a solution or carefully crafted set of solutions that could be reasonably expected to address all of the needs and concerns of each individual and family. The problem is one of economic calculation (see wiki at Mises website). The summary there is as follows –

“The problem referred to is that of how to distribute resources rationally in an economy. The free market solution is the price mechanism, wherein people individually have the ability to decide how a good or service should be distributed based on their willingness to give money for it. The price conveys embedded information about the abundance of resources as well as their desirability which in turn allows, on the basis of individual consensual decisions, corrections that prevent shortages and surpluses; Mises and Hayek argued that this is the only possible solution, and without the information provided by market prices socialism lacks a method to rationally allocate resources. Those who agree with this criticism argue it is a refutation of socialism and that it shows that a socialist planned economy could never work. The debate raged in the 1920s and 1930s, and that specific period of the debate has come to be known by economic historians as The Socialist Calculation Debate.

Ludwig von Mises argued in a famous 1920 article “Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth” that the pricing systems in socialist economies were necessarily deficient because if government owned or controlled the means of production, then no rational prices could be obtained for capital goods as they were merely internal transfers of goods in a socialist system and not “objects of exchange,” unlike final goods. Therefore, they were unpriced and hence the system would be necessarily inefficient since the central planners would not know how to allocate the available resources efficiently.[1] This led him to declare “…that rational economic activity is impossible in a socialist commonwealth.”[1] Mises developed his critique of socialism more completely in his 1922 book Socialism, an Economic and Sociological Analysis.”

There is also Frederic Bastiat’s 1850 essay (That Which is Seen, and That Which is Unseen) which comes into play where he discusses ‘unintended consequences’. Where good intentions are transformed into bad policies.

I am not saying safety nets shouldn’t exist. They should. What I am saying is the government and its agencies with their policies and programs are not necessarily the best vehicles to execute them. I would like to see less bureaucracy where the people are allowed to keep more of their earned income and make more decisions including charitable ones. When taxes and fees are deemed necessary for programs and collected by the government to be later redistributed, the level of government closest to the beneficiary is best suited to make a correct determination of the best use of funds.

I read through the first link on renegade landlords completely. It was a good article as they detailed some very disturbing cases. However, it was also missing important pieces of information such as the federal government’s involvement in the subprime mortgage crisis. It referred to it as the 2008 financial crisis as if it developed almost instantaneously with “corporate America’s advance into the U.S. rental market”. The subprime mortgage crisis had its beginnings with the Clinton administration policies. What I’m saying is this distorted market is a result of complex interactions between the government and corporate America. Nobody has clean hands here. And that’s one of the reasons why I believe in a limited government. A limited government that’s able to be a safety net when necessary. Not as a regular actor that grows beyond its original scope and takes on a role that was never originally intended for it.

I take the bait:

I don’t think anyone is talking about pure socialism which is what Hayek and Mies get so pissy about.

You write:

“When taxes and fees are deemed necessary for programs and collected by the government to be later redistributed, the level of government closest to the beneficiary is best suited to make a correct determination of the best use of funds.”

That describes feudalism. The Crown owns all the land and distributes it to the nobility. The serfs have their labor and they need to use the land. The nobility determine how best to disseminate land use privileges.

In other news:

The G7 just passed a 15% international tax on companies. In the US the biggest companies have been paying no taxes, so this new world order will decrease individual taxes significantly. That must make you so happy:)

Penelope